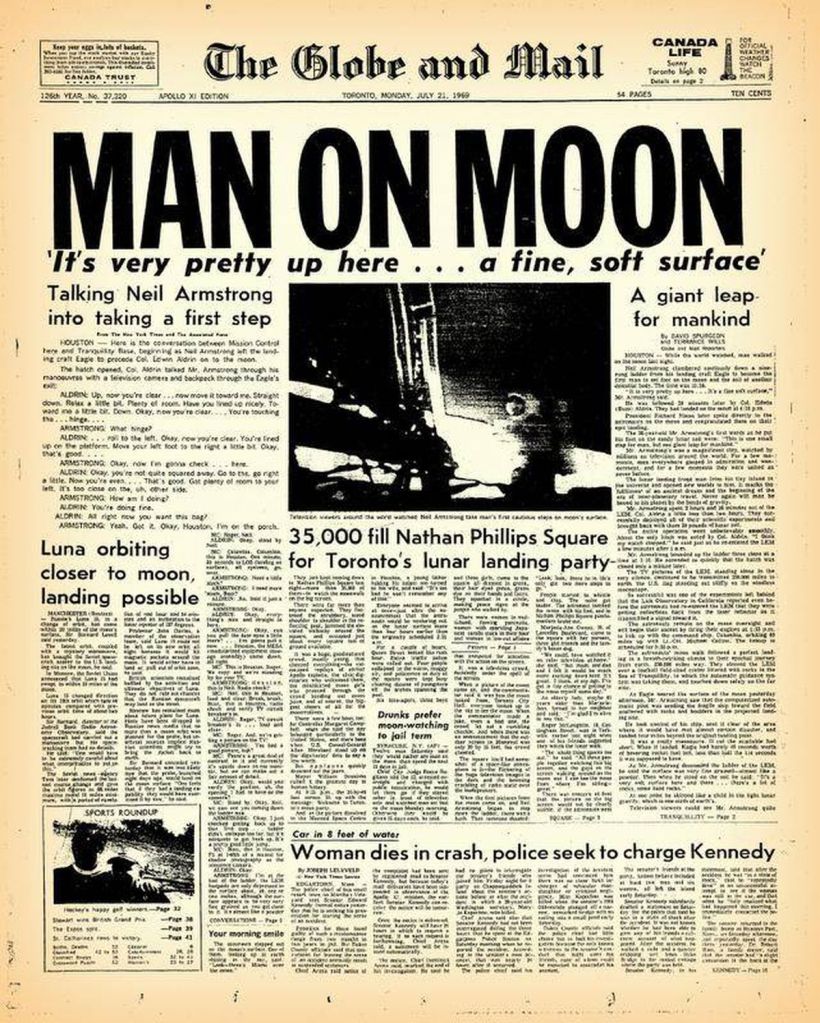

The Globe and Mail’s July 21, 1969, front page was intoxicating. Bold, green, three-inch high print announced MAN ON MOON. It reported 35,000 people breathlessly glued to a big TV screen in Toronto’s Nathan Phillips Square who cheered at 10:56 pm when Neil Armstrong stepped from the lunar module. Mayor Dennison delivered a brief speech calling it, “the greatest day in human history.” He may have been right. What he couldn’t know, and the Globe missed, were the important lessons contained in the paper that day, lessons that resonate today.

The moon adventure was the culmination of an effort begun by President John F. Kennedy on May 25, 1961. He had just returned from meetings with Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev. While Kennedy negotiated, Khrushchev had hectored. Kennedy became convinced that the Cold War was about to turn hot.

Upon his return, he called a special meeting of Congress and asked for a whopping $1.6 billion increase in military aid for allies and $60 million to restructure the American military. He called for a tripling of civil defense spending to help Americans build bomb shelters for a nuclear holocaust that, he warned, was a real possibility. The president also said: “I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” His popularity surged.

It was daring and presumptuous. Kennedy and his advisors had no idea of how the goal could be achieved – he set it anyway. The Soviets were far ahead of the United States in space exploration. But that day, and later, Kennedy expressed the courageous new effort in soaring rhetoric that appealed to America’s inspiring exceptionality and Cold War fears.

Kennedy did not then micro-manage the NASA project. He set the vision and got out of the way. He did not badger the agency regarding tactics or berate it over temporary failures. He didn’t question the intelligence or patriotism of those who politically opposed his ambitious goal. Rather, he met with them, listened, and tried to convince them of the value of bold ambition. He gave NASA the money it needed then trusted the scientists and engineers to act as the professionals they were. His vision and leadership spurred the team and survived his death.

Only a few years later, a smaller headline at the bottom of the Globe and Mail’s July 21 front page noted, “Woman dies in crash, police seek to charge Kennedy.” The story explained that Senator Edward Kennedy, the president’s brother, would be prosecuted for leaving the scene of an accident.

On July 18, with the Apollo astronauts approaching the moon and their rendezvous with infamy, Senator Kennedy had attended a party on Chappaquiddick Island for six women and two men who had worked on his brother Bobby’s doomed 1968 presidential campaign. While driving 28-year-old Mary Jo Kopechne back to her hotel, he took a wrong turn, then missed a slight curve on an unlit road and drove off a bridge and into eight feet of water.

Kennedy managed to escape the submerged car and later spoke of diving “seven or eight times” but failing to free Kopechne. He walked back to the party and was driven home. That night he consulted with advisors and then, eight hours after the accident, called the police. A coroner reported that an air pocket probably allowed Kopechne to survive for three or four hours before drowning. A quicker call for help, he concluded, would have saved her life.

In the 1990s, Edward Kennedy would become the “Lion of the Senate,” guardian of the Democratic Party’s progressive wing, and model for bi-partisanship. However, when he ran for his party’s nomination for president against the incumbent Jimmy Carter in 1980, many saw not a lion but liar – not the politician but the playboy. Chappaquiddick appeared to reflect the younger Kennedy borther’s belief that ethics, morality, and that rules and the rule of law applied only to others. Voters punished his conceit by withholding support.

It was all there in the Globe and Mail that day. We have the legacy of one brother who, despite his personal flaws, understood the nature, power, and potential of leadership. And we have the other brother who seemed, when it came to the crunch, to understand only the arrogance of privilege; the hubris to believe that he was above ethics, morality, and decency.

And now, we cringe as our leaders twist themselves into knots trying to appear like one Kennedy but somehow, too often, appearing as the other. Too many claim to have our short and long-term interests in mind while clearly considering only their own, or, at least, those of the donors who helped get them where they are.

Leadership is tough and, as JFK proved, it does not take a particularly nice person to do it well. Leadership is essential in a time of crisis whether the existential threat of something as consequential as the Cold War or a personal crisis that demands doing what is right according to principle and not the protection and advancement of oneself.

That dichotomous choice of leader and leadership is especially important right now as we navigate through the pandemic, economic recovery, climate crisis, and racial reconciliation. We need smart, serious, principled, honest people and we need them right now so that we might exert our agency in ways that will matter most to us and our grandchildren. We need the leadership not of the bridge but the moon.

(If you enjoyed this column, please send it to others on Facebook or your social media of choice and you might consider checking one of my books such as my latest “The Devil’s Rick: How Canada Fought the Vietnam War.)

CBR.com

CBR.com