Part of the joy of being an author is the privilege of travelling the country and meeting people who share a passion for books and ideas. Interviews are fascinating too because questions reveal the issues that are stirring interest. The questions are sometimes surprising.

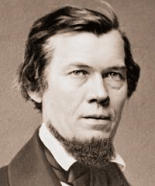

Last January I was speaking with an American journalist from Louisiana about my book dealing with Canada and the American Civil War. She said, “I read your book and admit I had never heard of John Macdonald. It seems like he was quite was a big deal.” “Yes,” I offered politely, “He was and is quite a big deal.” She continued, “So how would you explain Macdonald to our American readers in one sentence?” “Well,” I said, drawing a breath, “Macdonald is like America’s James Madison in that he led the writing of our constitution, and he is like your Thomas Jefferson in that he provided the ideological basis and political justification for the creation of our country, and he is like your George Washington in that he was our first chief executive that put flesh on the country’s skeleton while his every decision provided a precedent that resonates to this day; so our Macdonald was your Madison, Jefferson and Washington rolled into one man.”

I could have said much more. We can’t escape Macdonald. Every time we discuss the Senate, or the power of the prime minister, or the role of an MP, or government’s power we are revisiting his vision. We know that he created and built Canada. Less well known, however, is how he saved Canada.

In 1871, Canada was four years old. The American Civil War that had affected how and when the country had been created had been over for six years; but it was not really over. When the war began, Britain had declared itself neutral. That made Canada neutral too but still about 40,000 Canadians and Maritimers broke the law to don the blue and gray and fight. Canadians sold weapons to both sides and housed a Confederate spy ring that organized raids from Toronto and Montreal. John Wilkes Booth visited Montreal to organize Lincoln’s assassination. All of this and more led a great many Americans to call for revenge; generals, newspapers and politicians called for invasion and annexation.

Throughout the war, Britain had ignored its neutrality law and allowed ships to be bought or built then sold to dummy companies that turned them over to the Confederate navy. One such ship was called the Enrica. The Americans knew about it even while she was under construction at the Laird Yards in Liverpool in the fall of 1861. The British government allowed it to be built and then snuck down the Mersey to the Azores where it was refitted for war and rechristened the CSS Alabama.

The Alabama roamed the seas and eventually sank 64 American commercial vessels and a warship. Lincoln ordered it destroyed and the global hunt was on. In July, 1864, the Alabama was sunk outside a French port.

At the war’s conclusion, the United States continued its Manifest Destiny driven desire to have Canada. Annexationist Secretary of State William Henry Seward purchased Alaska in 1867. He explained that the purchase was merely a step in driving Britain out of British Columbia and eventually all of North America. But Macdonald stopped him by persuading those in Vancouver and Victoria to join Canada. Seward negotiated with Britain to purchase Rupert’s Land from the Hudson’s Bay Company – nearly all of what is now northern Ontario and the prairies. But Macdonald stopped him again by negotiating around the United States and buying it for Canada.

Seward had one card left to play. He argued that by allowing ships such as the Alabama to be built and bought that Britain had prolonged the Civil War and cost America money and lives. He added up everything from lost ships to increased maritime insurance rates and presented Britain with a bill totalling an astronomical 125 million dollars.

Britain would not, and in fact simply could not pay. Its economy would be crushed. Plus it needed what money it had to build its defence in light of growing troubles in Europe. It reacted to what became known as the Alabama claims by playing the diplomatic game of deny and delay.

By 1871, Ulysses S. Grant had become president. Like Seward, Grant hated the roles Canada and Britain had played in the war. He told his cabinet, “If not for our debt, I wish Congress would declare war on Great Britain, then we could take Canada and wipe out her Commerce as she has done ours, then we would start fair.” Grant’s Secretary of State Hamilton Fish spoke with the British minister to Washington Edward Thornton. He said that Grant would waive the entire Alabama reparation payment if Britain would simply hand over Canada. Thornton said the Canadians would probably not like it but that he would inform his government. Shortly afterwards, a conference was convened to settle the matter. Grant was pleased and said that if Canada was annexed then the Alabama claims could be settled in five minutes.

In February, 1871 five Americans, including Secretary of State Fish, welcomed five Brits to Washington. As a courtesy, the British allowed Sir John to be a part of their delegation. Macdonald knew that the future of his infant country was at stake. He took the proceedings so seriously that he even abstained from drink for the entire conference!

Macdonald maneuvered the agenda so that they began negotiating the American abuse of rules regarding inland fishing rights. It was an enormously important issue for Canada and he refused to budge an inch. But focussing on fishing was also a brilliant strategy for no matter how many other matters were raised Macdonald kept coming back to fishing. Every time anyone brought up the main question at hand – the Alabama claims – Macdonald talked to Fish about fish.

The Americans badgered him during the day. The British delegates badgered him every night. The Brits threatened him with a withdrawal of British military support. He was unmoved. They tried to bribe him with an appointment to Her Majesty’s Privy Council. He laughed them off. When cornered, Macdonald delayed by saying he needed to write home for advice. It was later discovered that his cables to the cabinet and governor general were being boomeranged back to Washington by Governor General Lisgar who had more loyalty to Britain than Canada. The backstabbing double-cross meant that British delegates knew exactly what Macdonald was doing and all of his fall back positions; but they could still not best him.

The conference ended after 9 weeks and 37 meetings. Macdonald won everything he had wanted. Fishing rights were settled in Canada’s favour. Because the Americans refused, Britain would pay Canada 4 million pounds in compensation for losses incurred in the Fenian Raids; Macdonald would use the money for railway construction. Free access to the American market for a number of Canadian products was guaranteed while Canadian tariffs could remain. Two concessions were more important than these and others. First, the Alabama claims would be settled by an international tribunal and it was agreed that the reparations for Canada swap was off the table. Second, it had been established that the ratification of the Washington Treaty would need approval by the American Congress, British parliament and by the Canadian parliament.

The Washington Treaty was the final battle of the American Civil War. It was the final episode of the American Manifest Destiny dream of Canadian annexation. Macdonald ensured that Canada could thrive because it would survive.

When he arrived back in Ottawa Macdonald delivered a four hour speech in the House. He did not strut. He did not gloat. Rather, he acted as a responsible statesman who respected Canadians sufficiently to explain what had been at stake and what had happened in all of its complex detail. He then went home and for the first time in over two months enjoyed a drink; perhaps more than one. He deserved it, he had saved his country, and that was quite a big deal.