The American Civil War continues to intrigue us because so many of the issues over which it was fought remain among us. Part of the fascination also springs from the horrible and heartwarming, the tragic and awe-inspiring stories of so many of the people involved. One such person was Sarah Emma Edmonds.

Edmonds was born to a poor New Brunswick farming family in 1841. When seventeen, her father ordered her to marry a man she had never met and who was nearly twice her age; she fled. A friend named Linus Seelye helped her escape by disguising her as a man. Besides adopting men’s clothing, she cut her hair, darkened her skin and changed her gait; she became Franklin Thompson. Edmonds was shocked by how differently she was suddenly treated. She was able to quickly find work and an apartment and to move about with a freedom she had never known. In her duplicitous but splendid liberation Edmonds was inadvertently illuminating women’s struggle and challenging the 19th century insistence that women couldn’t handle nor did they even want lives of self-sustaining independence.

After about a year, she did what many Maritimers and Canadians were then doing and moved to seek better opportunites in the United States. With an advance from a Boston publisher, she was soon back in the Maritimes selling Bibles. Her disguise had become so convincing that on a brief visit home she, for a while at least, even fooled her mother and sisters.

Shortly after moving to Michigan for better commissions, Fort Sumter fell and America tumbled into war. Both sides called for recruits in what President Lincoln said was a crusade to save the Union while President Davis claimed to be leading a struggle to defend his country against a northern aggressor. Over 600,000 would die. An extrapolation of population figures means that it would be the equivalent today of over 6 million deaths. Edmonds could have easily missed the slaughter by returning home but instead she enlisted.

She became one of about 40,000 Canadians and Maritimers who donned the blue or gray. Some, like her, were already in the United States working when they signed up. Many others left what is now Canada to enlist in order to seek adventure or earn a little money or to offer themselves for a cause in which they believed. As the war dragged on and recruitment became tougher, many Canadians were cajoled, tricked, or drugged to fill Northern enlistment quotas. Many American recruiting agents, called crimpers, even kidnapped Canadian children from school yards.

Meanwhile, Edmonds, in her Franklin Thompson personae, became the 2nd Michigan’s field nurse. It was believed that women could not be exposed to battle’s gore or men’s bodies and so nearly all nurses at the time were male. Without anyone’s knowledge, Edmonds was again invalidating gender stereotypes.

At Bull Run, or Manassas if you were from the South, the war’s first major battle, Edmonds watched Union troops move smartly forward but then the tide turned. Her field hospital was overwhelmed. She helped saw limbs and patch wounds and then moved through the thundering din and whizzing minié balls to rescue bloodied young men, all moaning for water and their mothers.

Later, she was part of the ill-fated Peninsula Campaign that took the Union army within sight of Richmond’s church steeples. As a mail carrier and dispatch rider she was often alone and suffered the cold fear of capture and the white heat of enemy fire.

Seeking greater service, Edmonds volunteered to be a spy and undertook ten treacherous missions. She donned various disguises and once, ironically, slipped through enemy lines dressed as a woman. Between assignments she nursed or rode messages and, at the battle of Williamsburg, was handed a weapon and fought.

In Kentucky, Edmonds was felled by emotional trauma and malaria. Coughing, shivering and enduring nightmarish hallucinations, she remained sufficiently lucid to realize that she could not seek treatment without ending her ruse. She purchased a train ticket and fled. She limped into an Illinois hotel and two weeks later emerged wan and weak to find herself listed as a deserter. She purchased a dress and left the fugitive Franklin Thompson behind.

By this point, desperation was trumping discrimination and women were being accepted as nurses so Edmonds re-enlisted as herself. Like other Canadians who served, nearly all for the North, she had grown used to meeting other Canadians. Happenstance reunited her with her New Brunswick beau Linus Seelye. At the war’s end they were married.

Edmonds wrote a bestselling book entitled Nurse and Spy in the Union Army. It offered great detail but kept the fact of her gender switch from the reader. While some later criticized her for embellishing some tales, the book remains a tremendous account of adventure, courage and determination and a valuable resource for understanding the war from a soldier’s view.

At an 1884 regimental reunion, her Michigan comrades were shocked that the man they had known was a woman. They discussed the fact that because Thompson had been disgraced as a deserter that Edmonds could not receive a pension. Many of them wrote letters to Congress detailing her bravery and contributions. Eventually the President granted her an honourable discharge and her monthly stipend began. By that point, hundreds of pension cheques were also crossing the border into Canada and the Maritimes. Canadian bones were in Civil War cemeteries throughout the North and South and 29 Canadians had won the Congressional Medal of Honor.

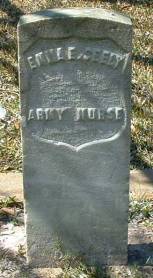

Edmonds died in 1898 at the Texas home of her adopted son. She was buried with full military honours in a Houston cemetery. Her headstone reads, with typical Canadian modesty, “Emma E. Seelye, Army Nurse.”

Sarah Emma Edmonds offered her life for a cause in which she believed and she served with élan. She proved that women were equal to men in will, courage, spirit and abilities. She represents the 40,000 other Canadians and Maritimers who offered themselves in a war that played an instrumental role in how and when Canada was born. Like the Civil War itself, Edmonds deserves to be remembered.

If you wish to discover more about Edmonds please check out Blood and Daring: How Canada Fought the American Civil War and Forged a Nation.